Category: All News Releases

Sharpen Up Your Tree Board

Urban Timber: Capitalizing on a Tree-mendous Resource

Farewell to an Idaho Tree Man, Mike Bowman

Administering a Timber Harvest

Administering a Timber Harvest

In technical terms, timber sale administration is the supervision of harvest activities to achieve silvicultural and economic objectives through sound logging practices and proper log utilization. In plain English, sale administration is telling a logger what you want before it’s too late. Communication and cooperation between a landowner and the logger is crucial. Very often, operators receive no feedback from landowners until a problem arises or the harvest is completed. But loggers need constructive input and criticism all during a harvest so they can adjust to the landowner’s desires. Here are some items to monitor while a harvest is in progress.

Falling Operations

Make sure only designated timber is being harvested. Trees marked reserve or

protected by a diameter limit should be found standing and in good condition when the dust clears. If overcutting is evident, let operators know immediately so they can adjust. Once in a while, it is impossible to avoid cutting or damaging a reserve tree. Be tolerant of an occasional glitch.

Also, determine if enough is being cut. Over the course of a harvest, thousands of board feet can be left in the woods in the form of small merchantable trees or unreasonably high stumps.

Loading Operations

Falling, skidding, and decking a tree does not insure it will get to the mill. Check landing debris and slash piles for merchantable logs and pieces. Mark them for retrieval.

Skidding Operations

Although the right trees are cut, they may not leave the woods. Occasionally a small merchantable tree, log, or chunk is missed or purposely forgotten. Mark any missed piece with flagging or paint. Let operators know they are expected to retrieve missed logs.

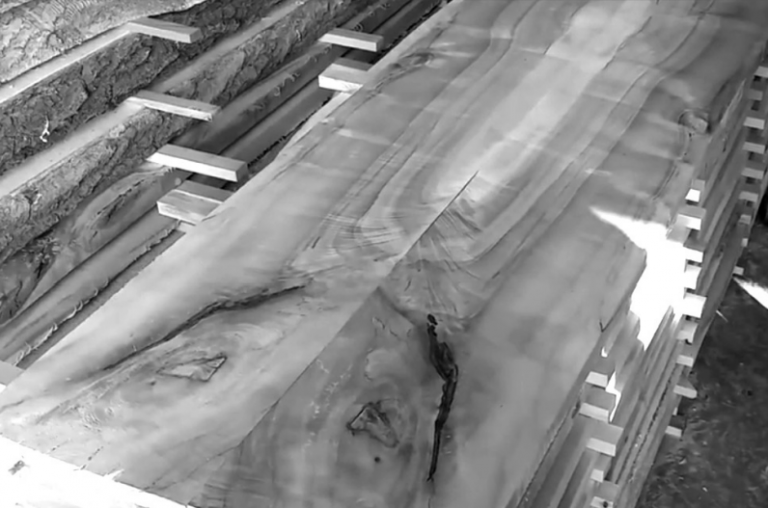

Log Quality

Any merchantability and utilization standards outlined in the contract should be consistently met. Examine manufactured logs at the landings. Determine if they are being cut to the required top diameter. Also check the necessity of long butting. Logs do not usually have to be totally free of rot to be merchantable. Contract standards should be met.

Forest Practices Requirements

Anyone conducting a timber harvest needs to be familiar with the rules and regulations of the Idaho Forest Practices Act (FPA). Copies can be obtained from your local IDL Private Forestry Specialist (PFS). Most of the rules protect water quality and land productivity. Normally, random inspections are conducted by the IDL, but a PFS will also visit upon request. The PFS can answer questions, provide assistance, or conduct a joint inspection. FPA rules should be incorporated into the sale contract and enforced.

Slash Disposal

Slash piles need to be relatively free of dirt and in a burnable condition. Have piles located a safe and required distance from green trees, streams, or ponds. If the adequacy of slash disposal is in question, contact your local fire warden or PFS for an inspection or advice.

Development and Other Items

The quality, progress, and completion of development work such as culvert installation, road construction, surfacing, etc. should be checked against the technical specifications of the contract. Also monitor the protection of fences, gates, ponds, roads, and other land improvements. Make sure garbage, filters, cans, etc. are cleaned up and properly disposed.

What about Conflicts?

A conflict can arise even with open communications and active administration. Questions and concerns should be taken to the sale purchaser or whoever is responsible for operations. It’s advisable to resolve any conflict as soon as possible. If an impasse is met, the contract should include provisions to halt operations and arbitrate disputes. Such action can put a damper on cooperation and should only be used as a last resort.

No harvest can be firmly administered without a well written contract. That document serves as the authority on practices, responsibilities, and procedures. A contract enhances sale administration but does not complete it. Administration is looking after a harvest while maintaining open and active communication and cooperation. Administer your harvest to achieve your goals.

For more information, contact your nearest Idaho Department of Lands Supervisory Area.

Locating a Timber Sale Purchaser

Locating a Timber Sale Purchaser

Experienced landowners know that a successful timber harvest requires planning. After management objectives, silvicultural prescriptions, and contractual requirements are formulated, a purchaser must be found. Usually, timber sale purchasers are responsible for logging operations. They can make you satisfied or disappointed in the results. There are plenty of competent purchasers in the market. Consulting foresters, logging contractors, log brokers, and saw mills all vie for stumpage. Names and addresses of local timber buyers can be obtained from your local IDL office, extension agent, or telephone directory. Once potential purchasers are known, the following procedures may be helpful in selecting a purchaser:

Write a Prospectus

A prospectus is a notice of request for bids with a brief description of the planned harvest. It usually lists the species, volumes, and products being sold, a legal description of the harvest area, a tentative sale date, the seller’s name and address, and any other pertinent information. Explain the exact form and markup wanted for the bid price.

Harvest Area Tours

Interested purchasers need an opportunity to examine the timber, understand the harvest objectives, review the sale contract, and estimate their logging costs. This can be accomplished with a tour of the harvest area. Arrange group or individual meetings, which ever is more convenient. The most important aspect of the tour is communication. Purchasers need to understand the seller’s goals, requirements, and desires so they can offer competitive bids. Likewise, sellers have an opportunity to glean information about logging and log markets. Comments or criticisms from seasoned woodsmen may be useful in revising the harvest plan.

Call for Bids

Customarily, bids are accepted two to four weeks after the prospectus is sent out. Depending on how the timber is being sold, bids are based on the price per unit volume (i.e. thousand board feet , cords, etc.), the price of the entire sale, or the costs of logging per unit volume. Loggers charge no fee for the “estimates” since they are trying to land a job. Always reserve the right to reject any or all bids.

Get References

Since the bidder of the highest amount to the landowner may not always be the best choice, have interested parties submit references with their bids. Investigate any likely candidate before awarding the contract. Choose contractors based on their track record as well as their price. Once a purchaser is selected and the contracts are signed, maintain communication. The purchaser deserves seller input and constructive criticism so adjustments can be made. Responsible contractors want to do a good job. Administer your harvest with this attitude in mind.

Sample Prospectus

Announcing the Sale of Timber and a Call For Bids

Joseph D. Landowner is accepting bids on approximately 255 MBF of timber located in the SWSW Section 37 and N2NW Section 38, Township 41 North, Range 8 West, B.M., as follows:

| Species | Net Estimated Volume (M) |

| Ponderosa Pine | 150 |

| Douglas-fir & Larch | 105 |

Bids will be based on dollars per thousand board feet by species, net scale, net amount to landowner. Bids for other species, namely white pine, grand fir (hemlock, subalpine fir), cedar, Englemann spruce, lodgepole pine, cedar products, and pulp, should also be offered to cover incidental cutting. Two or more references (names, addresses, and telephone numbers) should accompany the bid offer. The successful bidder will have one year from the date of sale to complete the harvest. Bids should be submitted before February 31, 1999. The seller reserves the right to reject any and all bids. A tour of the sale is scheduled for 8:00 a.m., February 14, 1999. We will meet in front of the Timbermine Grange Hall. Prospective bidders are encouraged to attend or make other arrangements to view the harvest area. For further information contact:

Joseph D. Landowner

P. O. Box 77

Timbermine, ID 87654

Phone: (208) 111-2222

Timber Sale Contracts

Timber Sale Contracts

Too often timber harvests are conducted with no more than a nod and a handshake between the parties involved. Although this procedure sometimes works, a written agreement is far better. Besides transacting the sale of timber, a contract also establishes communication, outlines practices to be followed, and clarifies responsibilities. All participants benefit when a foundation is established from the start. At first glance, preparing a contract might appear difficult, inconvenient, and downright formal. However, with a little help, writing a good sales agreement can be done with ease and satisfaction.

Sample Contracts

Since there is no such thing as a standard, concise, all purpose timber sale agreement, it’s good to start with a handful of examples. A variety of sample contracts can be acquired from your local Idaho Department of Lands office, timber company, soil conservation district, or extension agency. These generic contracts are often used as a basis for building a specific agreement and with them you can create a document tailor-made to fit your harvest situation.

The Document

Let’s look at the substance of a good timber sale contract. Most importantly, it is as short and simple as possible, with clear wording in plain language. The terms are understandable, executable and enforceable. Although such an agreement will not cover every eventuality, it will set some important guidelines.

A checklist is provided below which highlights appropriate information needed in a complete document.

Framing a Contract

Good sample contracts will address most major issues. Combine the best terms from several samples. Also, see your IDL Private Forestry Specialist for help. Although the PFS cannot write the contract, they can equip you with a menu of terms covering harvest practices and recommend clauses you should consider.

With all this information, you can mix, match, add, delete, or write your own terms of sale. Be careful, more restrictions usually result in higher logging costs. Just include enough requirements to accomplish your objectives and protect your interest.

Have a forester and a lawyer review your draft. There is safety in an abundance of counselors.

Administration

Finally, consider this. Your contract is a tool that protects your interests, conveys your desires, details procedures, and assigns responsibilities. But a successful timber harvest does NOT depend only on a well written document. It depends on communication and implementation. A contract not administered is a tool not used. Keep watch over your harvest operations. Administer your contract to achieve your goals.

Contract Checklist

Parties Involved*

- Names and addresses of both landowner(seller) and logger (buyer, purchaser, operator, contractor)

- Signatures of seller, buyer, and witnesses

- Date of agreement and place of

- execution

- Notarization of the contract

*For the purpose of this article, it is assumed the landowner

is the timber owner.

Performance of Buyer

- Duration of contract with or without a provision for extension or assignment

- Cash or surety bond posted by the buyer to ensure full and faithful compliance with all contractual obligations

- Clause to terminate operations due to

- noncompliance

- Liability and Workers’ Compensation Insurance requirement

- Clause for arbitration of disputed contract execution by buyer or seller

- “Force Majeure” clause for release of obligations by buyer or seller due to fire, flood, strike, or other catastrophe

Payment

- Terms of payment (how, when, and to whom)

- Scaling (if applicable, including the scale to be used, who will scale, where, and when)

- Penalty for cutting undesignated timber

Property Involved

- Complete legal description of the harvest area with a map to scale

- The party responsible for locating establishing property corners, lines, and harvest area boundaries

- Timber being sold (identified by species, products, estimated volumes, unit of measure, net or gross scale price per unit, cutting designations of tree marking)

- Ownership of timber and when title passes from seller to buyer

Harvest Practices

- Compliance to the Idaho Forest Practices Act

- Compliance to the State slash hazard (disposal) and fire protection laws who piles, burns, reduces, and pays the State

- Size and types of logging equipment

- Utilization guidelines (maximum stump height, log size, merchantable tree and log standards, minimum top diameter

- Location and standards of roads, landings, and skid trails

- Protection of fences, gates, roads, livestock, structures, etc. Post-logging “touch-up” of roads, trails, culverts

- Clean-up of garbage and waste

- Party responsible for acquiring and maintaining access and right-of-way

For more information, contact your nearest Idaho Department of Lands Supervisory Area.

Forest Management 3: Timber Sale Contracts

Forest Management 2: Planning a Timber Harvest

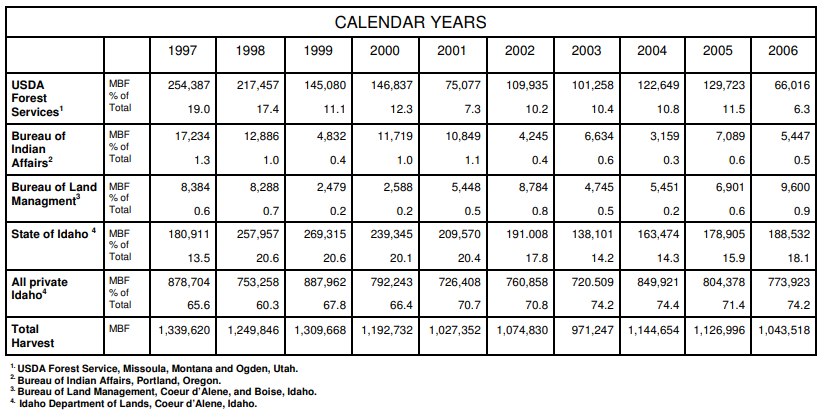

Forest Management 1: Idaho Timber Facts

Forest Management 9: Snag Management