The Root of the Problem: Roots and Turfgrass

By Gerry Bates

IDL Southern Idaho Community Forestry Assistant

Hidden away beneath the soil, roots quietly, almost mysteriously, go about doing their job. The tree root system may be described as unseen and unappreciated. The relationship between tree root systems and the characteristics of the soils in which they grow has a greater influence on tree health than any other single factor.

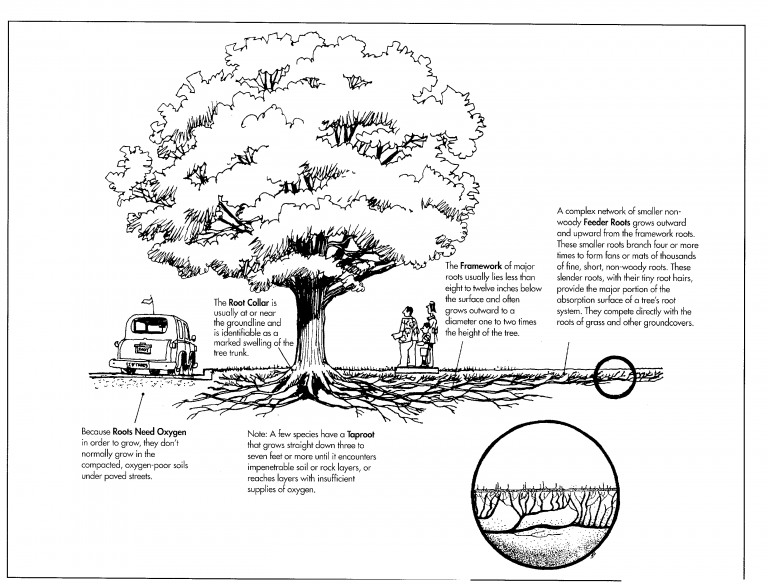

When a tree seed germinates, the first or primary root grows down in the soil in response to gravity. Secondary roots then branch off horizontally, with subsequent branching into tertiary roots. Absorption of water and mineral nutrients is the function of the very fine, non-woody roots called feeder roots. As the roots grow, they become woody and lose their ability of absorption.

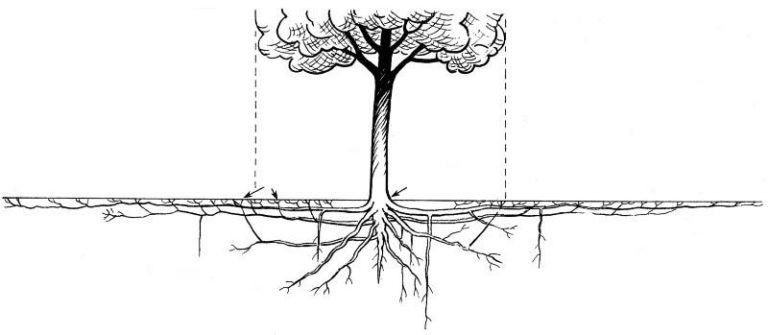

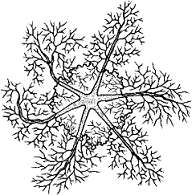

These larger woody roots then function as the transport system for water and nutrients for the new feeder roots as they develop. They are also the tree’s system of anchorage and a food storage area. The resulting system thus consists of several main transport roots that extend radially and horizontally from the tree base and divide into ever-smaller roots, each ending in a dense mass of fine feeder roots.

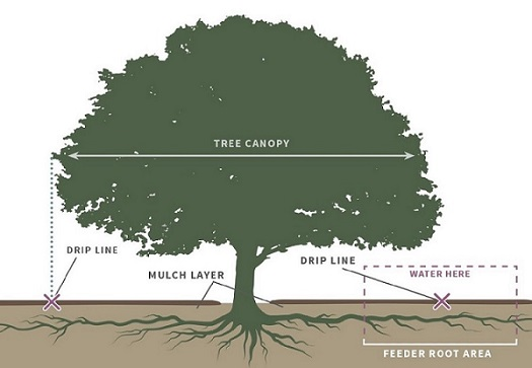

Because of the horizontal growth pattern on the tree root system, over 90 percent of the entire tree’s root mass are located in the top two feet of the soil. Tree roots can also extend far beyond the tree’s “drip line”, usually radiating out from the trunk a distance of up to two times the trees height. This growth pattern is the direct result of root biology. As soft feeder roots become woody, their absorption capacity is lost and new feeder roots must be produced.

Tree root absorption is dependent on continued growth of new roots. Roots only grow where the physical and chemical environment is correct. This environment consists of factors such as temperature, moisture, aeration, soil pH, nutrient supply, and soil structure. Roots also need oxygen, and new root growth is restricted where oxygen is limited. In most soils, a satisfactory growing environment exists only within the top few feet. In fact, the greatest proliferation of tree roots will be found in the transition zone at the soil surface.

Any tree growing in a well-fertilized lawn is well fertilized. Because the tree’s feeder roots are in the same soil volume as the grass roots, both have access to all the applied fertilizer. However, we need to be aware that the tree and turf are competing for those nutrients. Other lawn treatments can pose a threat to the trees

Turf herbicides can be very damaging to trees when absorbed by the roots. The herbicide does not have to move down in the soil to be damaging to the tree roots, these roots are with the grass and weed roots. Restricting herbicide application to the lawn outside the tree drip line may not be sufficient as we do not know how far the roots extend.

Roots do not seek water; they grow where moisture is available. During summer months, outdoor water use typically accounts for forty to sixty percent of residential water use and as much as eighty percent on hot, dry days.

With so much water being used to water lawns, gardens, and shrub areas, landscape watering becomes an obvious target for saving water. This year, the wet, cool spring days made it unnecessary to provide additional irrigation for proper tree growth. But, as the humidity decreases and the temperature increases, so will your trees need for water.

Lawns require moisture in the top two to three inches of soil to remain green and healthy. Since most of the absorbing roots of most trees are located in the top twelve to eighteen inches of soil, it’s easy to see why it’s necessary to provide additional deep watering in the dry months.

To be sure that enough water is being delivered to the root system of your trees, run a soaker hose around the drip line of the tree for several hours about twice a month. If you soil is sandy or gravelly, do this even more often.

To retain more of the moisture you use, mulch around the trees. Mulch reduces weed growth, helps to hold the water in the soil, keeps lawnmowers and weed eaters away from the trunk, and looks good. Mulch is often a trees best friend. Avoid watering the lower trunk of the tree, as this can lead to root crown rot.

Be aware that trees can also be easily over watered. Lack of oxygen due to excess moisture suffocates roots, changes the chemical composition of essential elements and can lead to root deterioration. Trees that have experienced flooded conditions are prone to toppling due to root loss and wet soils, and they suffer a higher incidence of root rot.

Tree species differ in their watering requirements. Some are adapted to long, dry summers and can tolerate four or five months without rain or irrigation. Others are accustomed to fairly regular rainfall and will begin to show stress after several weeks without adequate moisture.

Remember to plant trees in sites where the conditions for the species are favorable and the tree has the best chance to establish and grow properly. If a tree is not sited properly, soil amendments, mulching, and careful attention to its irrigation will be required.