Category: Urban and Community Forestry Library

Structural Pruning for a Resilient Urban Forest

By Garth Davis

IDL Northern Idaho Community Forestry Assistant

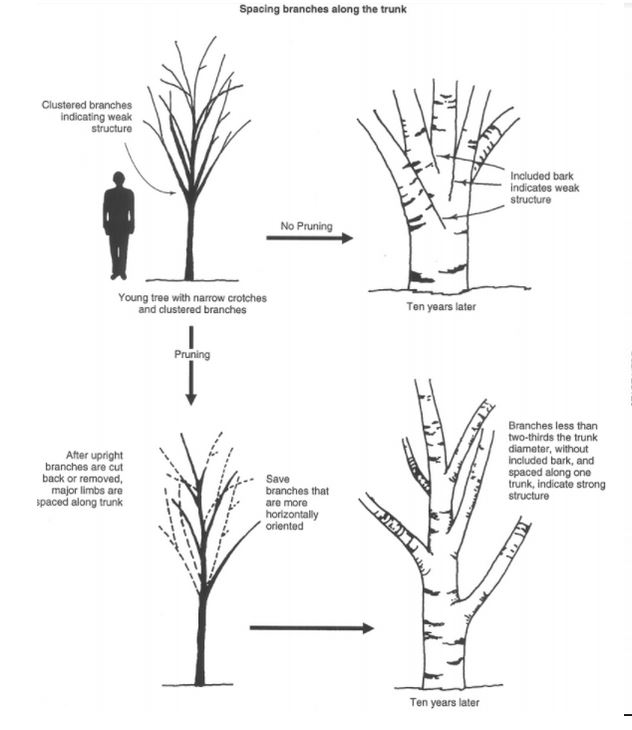

Choosing quality trees to be planted on public property and picking a site where they can thrive into maturity are great ways to make your urban forest more resilient. A structural pruning cycle for young trees will enable your trees to better withstand extreme weather events such as wind and heavy snow, giving large growing trees a better chance to become ecosystem service providers.

There are economic benefits to structural pruning, you get to address tree problems with hand pruners, hand saws on an orchard ladder instead of letting the problems grow into something that needs chainsaws, tree climbers, or bucket trucks. More large trees thriving in your community provide more ecosystem services which is good for a town’s bottom line. Important ecosystem services include improved air quality and stormwater retention and mitigation.

The goal of structural pruning is to create and maintain a single main stem in a tree through several pruning events while the tree is young, usually starting after the tree is established in the landscape. The pruning principles of removing or subordinating codominant stems, controlling the size and location of scaffold branches, and remediating weaker branch attachments creates a tree whose structure can withstand higher wind speeds and heavier snow loads.

A helpful video on structural pruning from Bartlett Tree Experts can be found here. Dr. Gilman’s lab at the University of Florida is also a good resource for pruning tips and can be found here.

As with any pruning you do, knowing the species you are pruning and how it will react to pruning is important. Species that grow faster or are more prone to suckering will need to be put on shorter pruning cycles, while species that are slow growing will need more time between pruning events. Sucker maintenance in between major pruning events may be necessary on some species to make sure you aren’t creating a bigger problem.

North Idaho is growing as fast as anywhere. This growth creates opportunities for communities to implement structural pruning programs. Within the last few years both Priest River and Sandpoint have had large (relative to their size) plantings installed in their downtown cores. These plantings represent a large investment in the beautification of the town centers. To better help the new trees thrive, both communities took advantage of the technical assistance offered by the Idaho Department of Lands to train their employees through a pruning workshop and practice sessions.

The Priest River and Sandpoint employees were taught the principles of structural pruning, watched while the Community Forestry Assistant demonstrated the principles while pruning several of the new trees, then they took the pruners and saws and made the cuts under the guidance of the Community Forestry Assistant. Through this process the city employees became familiar with the species they would be maintaining in these high-profile plantings.

If you are interested in having your community’s employees trained in the principles of structural pruning contact the Idaho Department of Lands Community Forestry Assistant in your area to begin the process.

The Root of the Problem: Roots and Construction

By Gerry Bates

IDL Southern Idaho Community Forestry Assistant

Construction or landscaping activities that cut the roots of mature trees or compact the soil around trees will often lead to death of all or part of the tree. This damage may not be visible for as long as two years after the damage was done and the injurious activity is forgotten. By far, the most common and serious root injuries we inflict on mature trees are from changing the soil’s aeration.

Adding soil, even as little as a few inches, over the existing surface places the major root mass that much deeper. With less oxygen, the roots may die quickly, and unless new roots can be rapidly produced in the surface soil, the tree will die. Soil compaction has the same effect, reducing the soil’s air supply plus creating a physical barrier for new root growth.

Recreation and construction areas that receive regular foot or vehicle traffic are prone to compaction. Keep in mind that tree roots do not respect property lines. The effects of these activities in one area may affect your neighbor’s trees, and vice versa. The soil ecosystem’s health is key to your tree’s overall health. Soil compaction from construction can result in the reduction of soil pore space. Smaller pore spaces in the soil causes a reduction of oxygen and water available to the roots and can lead to a decline in tree health and eventual failure.

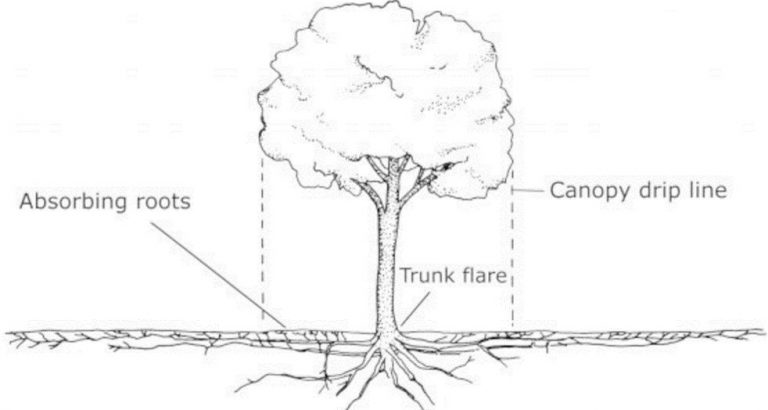

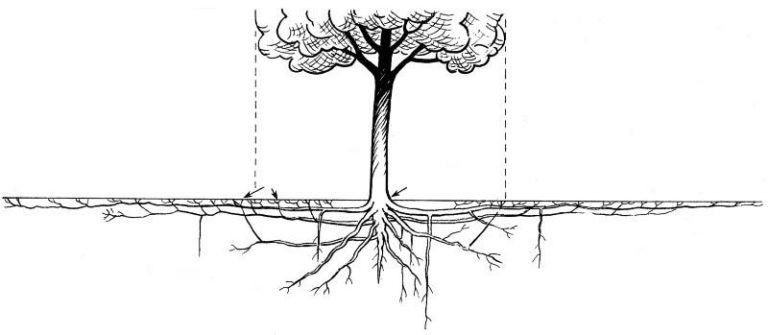

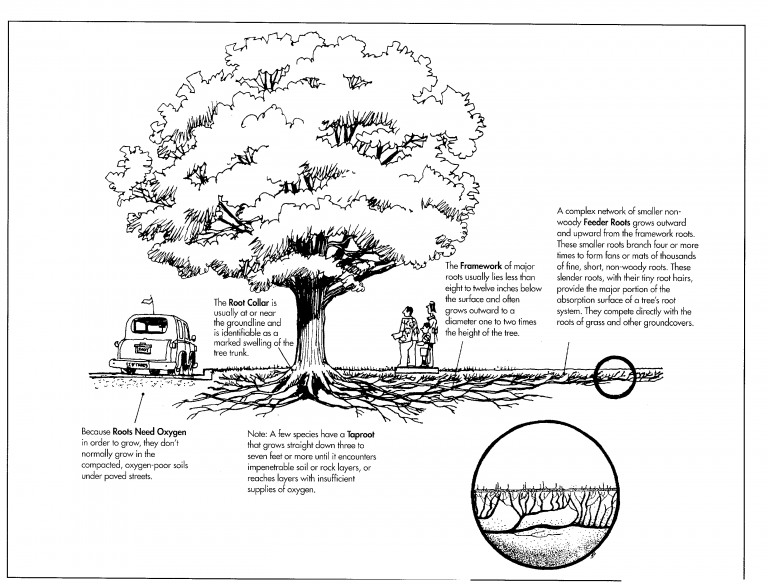

Damage to tree roots during construction or landscaping activities can happen quite easily. Most of the important fine absorbing roots for mature trees are located within the first 6 inches of the soil profile. These important roots typically extend beyond the tree’s canopy and are often damaged during landscaping or construction activities.

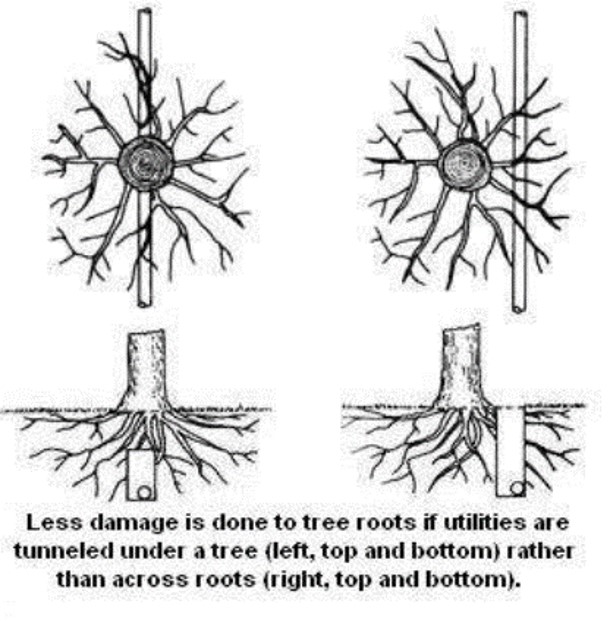

Root damage is most common when utility companies trench near trees to install new lines or to repair existing underground lines. The amount of damage to the tree depends on the proximity of the damage to the root collar and the percentage of root loss. Severing one major root can kill 15-25% of the entire root system.

Severe root loss during construction can result in a decline in overall tree health and appearance. Symptoms from construction damage often occur over several years after the initial trenching or construction and can lead to whole tree failure. Tunneling under the roots using a trenchless device is a good solution to avoid damaging tree roots.

Right Tree, Right Place – Ensure Your Trees will Thrive

Michael S. Beaudoin

Community Forestry Program Manager

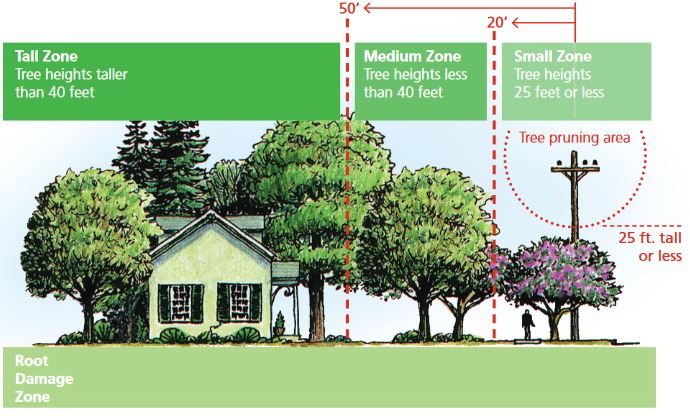

Proper tree selection and placement is commonly referred to as “Right Tree, Right Place.” This commonly refers to proactively avoiding tree conflicts with utility lines.

Researching your climate, soil conditions, and tree species profiles for your planting project will also ensure you pick the right tree for the right place.

Trees are divided by their mature size into three different classes. Different tree species have very different mature heights and it is important to keep this mind when planting near utility lines or homes.

These tree classes include:

- Class I: Trees that are safe to plant near power lines. These trees grow no taller than 25 feet.

- Class II: Should not be planted closer than 25 feet from power lines depending on the mature canopy size. This tree class grows no higher than 40 feet.

- Class III: Are large trees that should be planted at least 35 feet away from the house to minimize damage to houses and other buildings. This tree class grows to 60 feet or taller.

Utility-friendly trees for Idaho include Mountain Ash (Sorbus aucuparia), Eastern Redbud (Cercis canadensis) and select cultivars of Flowering Dogwood (Cornus florida). More information on utility-friendly trees can be found from Avista here and Idaho Power here.

Ensuring your trees don’t conflict with utilities is very important, but is also only part of the picture for tree selection and placement. The hardiness zone and the species profile of the selected trees are also important considerations when selecting and planting new trees.

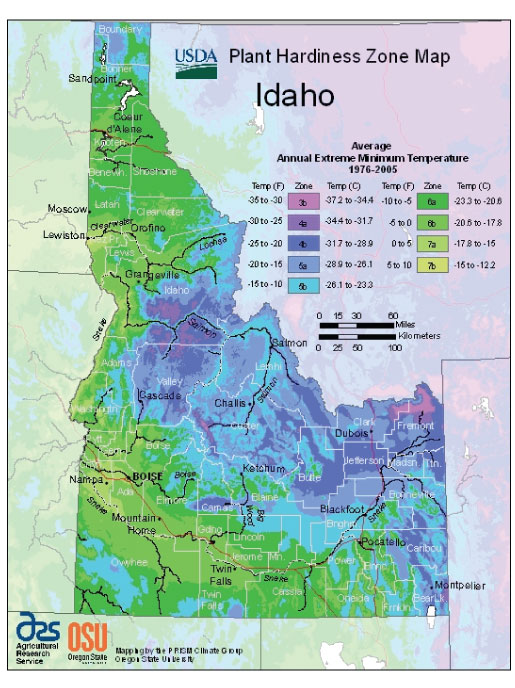

Knowing the site conditions of your planting area will help you identify tree species and cultivars that will thrive in the proposed planting area. Knowing your USDA plant hardiness zone is good place to start. Plant hardiness zones are based on the average low temperature for a given area. Hardiness zones in Idaho vary dramatically. For example, much of the Treasure Valley falls into hardiness zone 7a, whereas Idaho Falls falls into hardiness zone 5a due to Eastern Idaho’s harsher winters. You can find your plant hardiness zone here.

Your local soil and site conditions such as pH, soil texture composition, and wind exposure should also inform your tree species selection and placement. The Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) provides much of this information for your address on the Web Soil Survey website here.

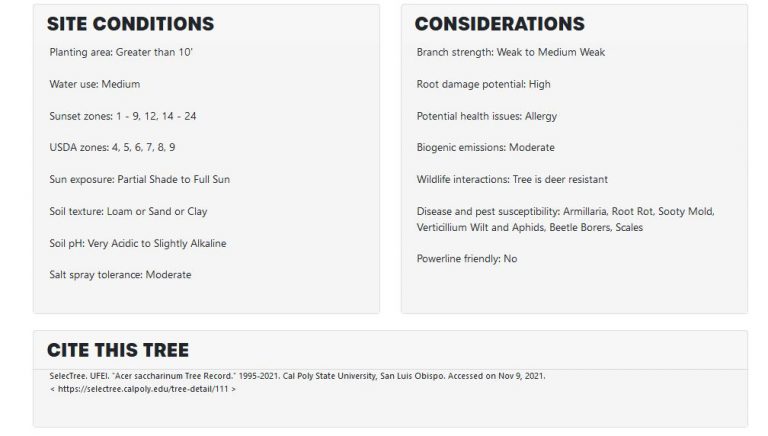

Maintaining a species profile of potential tree species for your project or common tree species within your region is a good practice for any arborist. Species profiles provide important information like mature tree characteristics such as canopy width, maximum tree height, and growth rate. Species profiles also provide known common issues with a particular species or cultivar such as pest susceptibility or a proclivity for developing codominant stems.

Two great resources for gathering information on tree species include:

- Treasure Valley Tree Selection Guide (Co-authored by many arborists within the Treasure Valley)

- SelecTree (An online tree species profile database managed by Cal Poly)

“Right-Tree, Right-Place” is a great educational campaign that reminds us to make informed tree selections and decisions near utility lines. Choosing the right tree for the right place also includes evaluating the site conditions and the tree species growth characteristics for your planting project. Researching the size class of the trees in your planting project and having a handy species profile of each species in your proposed tree planting plan will help ensure your new trees thrive and don’t conflict with utilities.

Equity in Idaho’s Community Forests

Michael S. Beaudoin

Community Forestry Program Manager

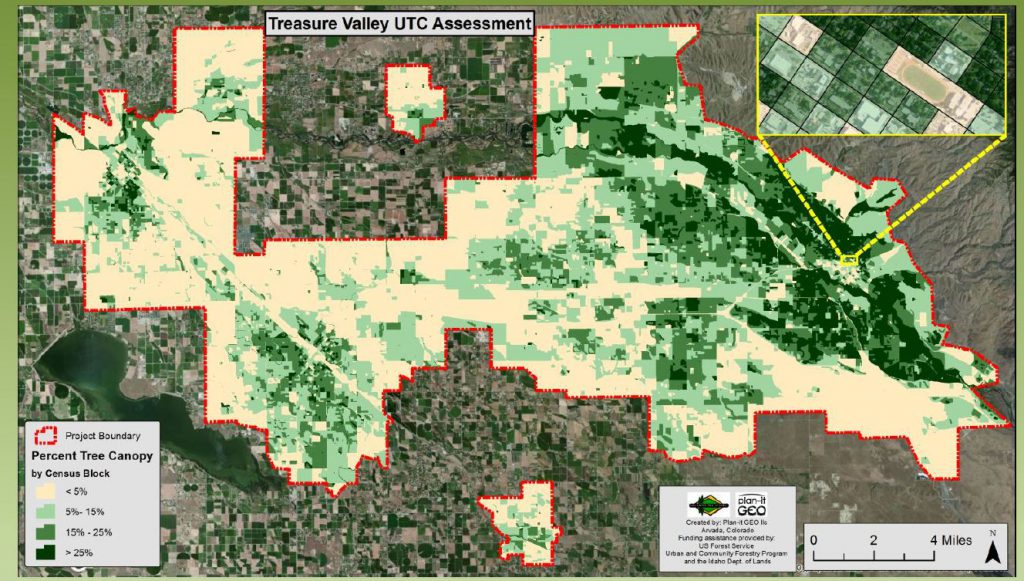

Equity is a current hot-button topic in urban and community forestry. Our urban and community forests provide many important social and ecological benefits to our residents. Higher tree canopy coverage in residential areas often correlate with higher property values, better physical and mental health, and a reduction in energy usage.

Recent research into urban canopy coverage in American major cities indicates that our low-income residents, renters, and minority groups often live in areas with very low canopy coverage and don’t receive the associated benefits of higher canopy coverage. Some recent research on this topic can be found here and here.

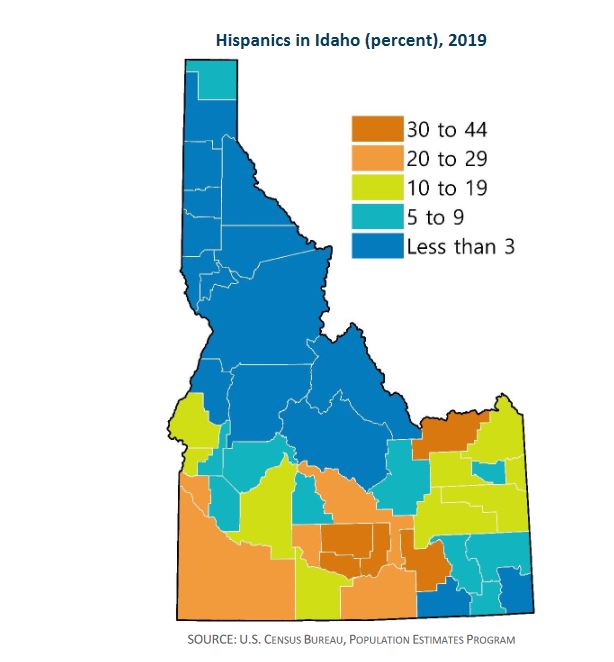

Although there isn’t a lot of peer-reviewed research on this topic for Idaho’s communities, recent census data and our canopy assessment data shows that we could improve our outreach to our historically under-served residents.

Each year, the 17 western state urban forest program managers meet for our annual training conference. Idaho hosted this year’s conference with the theme of “Advancing Equity in Urban and Community Forestry”. Each program manager shared how their programs assist each state’s underserved residents. Some states, such as Washington and California, incorporate equity considerations into their grant programs and canopy assessments. The program resulted in valuable information sharing and connections to help improve our program delivery throughout Idaho.

The UCF program manager’s conference also included several guest speakers on equity. Ian Scott, Chair of the Pacific Northwest ISA’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) committee shared how the Pacific Northwest ISA chapter is making progress on assisting underserved residents and planning virtual arbor chats to share more information on diversity and inclusion.

Dr. Jaap Vos also spoke to the program managers about equity considerations in urban and community forestry. Dr. Vos is a professor of planning and natural resources at the University of Idaho. Dr Vos shared some of his research into how open spaces and canopy coverage increases livability and property values in the Treasure Valley. Dr. Vos’ page can be found here.

This annual learning conference has encouraged us to utilize our tree canopy data to identify equity gaps within our program. We plan to utilize the data from our canopy assessments to identify areas within our municipalities that lack urban canopy coverage, shade trees, and access to open spaces. Upcoming census data and our existing canopy data will help us identify potential planting and outreach project areas for our program.

Our program is also assisting underserved groups by encouraging diversity candidates to apply for the Society of Municipal Arborist’s MFI program. The MFI program is a high-level leadership program for arborists to master leadership and public administration skills. Recent successful attendees from our program included arborists from our underserved Hispanic communities like Nampa and Caldwell.

The Idaho community forestry program is also committed to increasing opportunities for women in the arboriculture and the science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields. To this end we plan to sponsor a scholarship for a woman to attend SMA’s MFI leadership development workshop in the near future.

Expect more information in the winter edition of the newsletter on our progress towards better assisting our historically underserved residents.

Tree I.D. Made Easy

Virginia Tech University’s vTree can help you identify more than 1000 woody plants from all over North America. Each tree entry contains a fact-sheet that provides an in-depth description, range map, and color images.

The app is free and can be found in the Apple store here or in the Google play store here.

Key Features include:

- More than 1000 woody plants from all over North America

- Over 6,500 color photographs of leaves, flowers, fruit, twig, bark, form, and range map for each species

- In depth description of all plant parts

- Narrows species list based on your location and elevation using the phones GPS, network signal or user entered location

- Search for species by a key word, e.g. maple

- Identify species by answering a series of simple questions. A picture is displayed showing what is being asked.

- Navigate between species with a push of a button.

- Send a tree question to “Dr. Dendro” a tree expert at Virginia Tech

The Root of the Problem: Roots and Turfgrass

By Gerry Bates

IDL Southern Idaho Community Forestry Assistant

Hidden away beneath the soil, roots quietly, almost mysteriously, go about doing their job. The tree root system may be described as unseen and unappreciated. The relationship between tree root systems and the characteristics of the soils in which they grow has a greater influence on tree health than any other single factor.

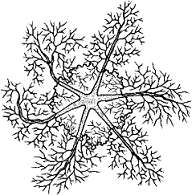

When a tree seed germinates, the first or primary root grows down in the soil in response to gravity. Secondary roots then branch off horizontally, with subsequent branching into tertiary roots. Absorption of water and mineral nutrients is the function of the very fine, non-woody roots called feeder roots. As the roots grow, they become woody and lose their ability of absorption.

These larger woody roots then function as the transport system for water and nutrients for the new feeder roots as they develop. They are also the tree’s system of anchorage and a food storage area. The resulting system thus consists of several main transport roots that extend radially and horizontally from the tree base and divide into ever-smaller roots, each ending in a dense mass of fine feeder roots.

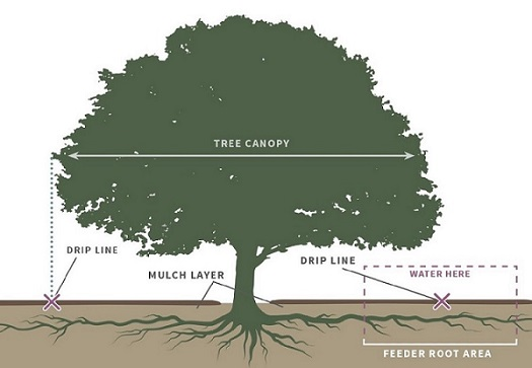

Because of the horizontal growth pattern on the tree root system, over 90 percent of the entire tree’s root mass are located in the top two feet of the soil. Tree roots can also extend far beyond the tree’s “drip line”, usually radiating out from the trunk a distance of up to two times the trees height. This growth pattern is the direct result of root biology. As soft feeder roots become woody, their absorption capacity is lost and new feeder roots must be produced.

Tree root absorption is dependent on continued growth of new roots. Roots only grow where the physical and chemical environment is correct. This environment consists of factors such as temperature, moisture, aeration, soil pH, nutrient supply, and soil structure. Roots also need oxygen, and new root growth is restricted where oxygen is limited. In most soils, a satisfactory growing environment exists only within the top few feet. In fact, the greatest proliferation of tree roots will be found in the transition zone at the soil surface.

Any tree growing in a well-fertilized lawn is well fertilized. Because the tree’s feeder roots are in the same soil volume as the grass roots, both have access to all the applied fertilizer. However, we need to be aware that the tree and turf are competing for those nutrients. Other lawn treatments can pose a threat to the trees

Turf herbicides can be very damaging to trees when absorbed by the roots. The herbicide does not have to move down in the soil to be damaging to the tree roots, these roots are with the grass and weed roots. Restricting herbicide application to the lawn outside the tree drip line may not be sufficient as we do not know how far the roots extend.

Roots do not seek water; they grow where moisture is available. During summer months, outdoor water use typically accounts for forty to sixty percent of residential water use and as much as eighty percent on hot, dry days.

With so much water being used to water lawns, gardens, and shrub areas, landscape watering becomes an obvious target for saving water. This year, the wet, cool spring days made it unnecessary to provide additional irrigation for proper tree growth. But, as the humidity decreases and the temperature increases, so will your trees need for water.

Lawns require moisture in the top two to three inches of soil to remain green and healthy. Since most of the absorbing roots of most trees are located in the top twelve to eighteen inches of soil, it’s easy to see why it’s necessary to provide additional deep watering in the dry months.

To be sure that enough water is being delivered to the root system of your trees, run a soaker hose around the drip line of the tree for several hours about twice a month. If you soil is sandy or gravelly, do this even more often.

To retain more of the moisture you use, mulch around the trees. Mulch reduces weed growth, helps to hold the water in the soil, keeps lawnmowers and weed eaters away from the trunk, and looks good. Mulch is often a trees best friend. Avoid watering the lower trunk of the tree, as this can lead to root crown rot.

Be aware that trees can also be easily over watered. Lack of oxygen due to excess moisture suffocates roots, changes the chemical composition of essential elements and can lead to root deterioration. Trees that have experienced flooded conditions are prone to toppling due to root loss and wet soils, and they suffer a higher incidence of root rot.

Tree species differ in their watering requirements. Some are adapted to long, dry summers and can tolerate four or five months without rain or irrigation. Others are accustomed to fairly regular rainfall and will begin to show stress after several weeks without adequate moisture.

Remember to plant trees in sites where the conditions for the species are favorable and the tree has the best chance to establish and grow properly. If a tree is not sited properly, soil amendments, mulching, and careful attention to its irrigation will be required.

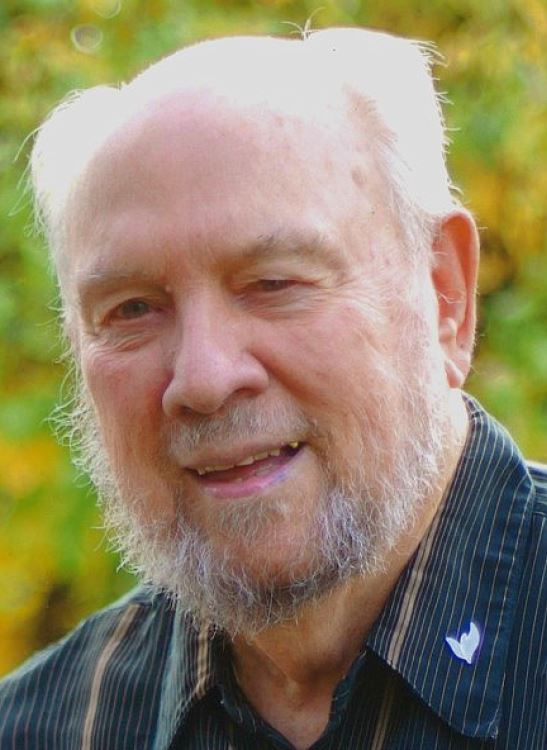

Honoring the Contributions of Del Jaquish

By Craig Foss

Idaho State Forester

We have the unfortunate task of sharing with you that Del Jaquish passed away. Del played a critical role in assisting IDL with our Urban and Community Forestry Program in the late 1990s and early 2000s, serving as the Acting Program Manager and as a member of the Idaho Community Forestry Advisory Council.

Del was raised in Fresno and Sanger California and attended Reedley College. He obtained his BS in forestry from the University of Idaho in 1953. He served in the United States Army from 1953 to 1955. Del started working for the United States Forest Service seasonally while in high school and college, eventually becoming a smoke jumper, and after receiving his forestry degree and serving in the military he was hired as a District Ranger, serving multiple Ranger Districts in Idaho and Montana.

His outstanding communication skills led to multiple promotions throughout his 33-year career, eventually retiring as Deputy Director for Public Affairs in the Washington D.C. office. After retiring from the USFS, Del and his wife Bev settled in Post Falls, where he quickly became involved in urban/community forestry. He shared his love of people and his forestry expertise as Post Falls’ City Forester, while also helping the cities of Wallace, Kellogg and Smelterville develop local programs.

Del continued working with Idaho communities well into his 70s, when his eyesight failed. He and Bev moved to Garden Plaza Assisted Living in 2018, with Bev passing in 2019 and Del passing in late April 2021 – just shy of his 92nd birthday.

For all of us at IDL, and for many of you who knew Del, we are thankful for his contributions to our statewide program. And we’re all the better for having had the opportunity to spend time with such an exceptional human being!

Forest Health Update: Bark Beetles FAQs

By Erika Eidson

IDL Forest Health Specialist

What are bark beetles?

Bark beetles are a group of insects that spend almost their entire life beneath the bark of trees. They tunnel in the moist inner bark, lay eggs and these develop into larvae or grubs. The tunneling kills trees by girdling them (cuts off the supply of nutrients). Adults emerge later to infest other trees in late spring or early summer. For more information, please see the IDL bark beetle fact sheet.

Certain bark beetles can reproduce in green logs, uprooted trees and green firewood if the inner bark is moist in April and May.

Bark beetles are cold blooded, so they will develop faster during warm weather. Drought and hot, dry summers are stressful for trees and increase the success of bark beetles.

What bark beetle species cause the most problems?

Pine engraver: prefers damaged ponderosa and lodgepole pine trees and slash. It has multiple generations per year. Pine engraver overwinters as an adult, and flies early in the spring as temperatures warm. It infests green pine logs > 3” diameter in April and May and lays eggs. These eggs develop into adults approximately 6 weeks later.

The emerging adults will infest more down material if it is available, if none is available they will attack standing trees in June and July. Normally, the eggs laid in these standing trees develop into adults that overwinter. However, in warm and dry years, a third generation of beetles can attack and kill additional trees later in summer and fall. For more information, please see the IDL pine engraver fact sheet.

Douglas-fir beetle: can infest damaged Douglas-fir or down western larch. This species has one generation per year. It overwinters as an adult, and flies early in the spring and prefers green, down material. Beetles tunnel in the bark, lay eggs and one generation of larvae develop in the logs or down trees. Adults then overwinter under the bark or in the forest litter. For more information, please see the IDL Douglas-fir beetle fact sheet.

Spruce beetle: can attack damaged spruce and takes one or two years to develop in infested logs, depending on temperature. Spruce beetle outbreaks can be very severe if many host trees are present. Needles on fatally-attacked trees may remain green for longer.

What is the best way to avoid bark beetle problems?

The best course of action is to NOT have down, green material available in spring when the bark beetles emerge. If logs become infested, remove or destroy them before beetles can emerge.

What if I live in urban or suburban areas? Some counties or municipalities will accept woody material at transfer stations or landfills. The material is often chipped to be used for other purposes such as mulch or industrial fuel.

If you can’t remove the damaged trees or slash, try to make them unsuitable for bark beetle reproduction. If salvage is not practical, damaged trees can be safely burned if allowed, debarked or chipped. Planer chainsaw attachments, such as the LogWizard, can be effective tools for bark removal. If this is not practical, broken tops or uprooted trees can be cut into smaller pieces and the limbs removed. Placing them in sunny areas will assist the drying process. The idea is to help the logs to dry out as quickly as possible.

Can I save the wood for use as firewood?

If the species is not pine, firewood cut into 16” pieces and split may be infested by beetles this spring, but it is unlikely that any beetles will emerge in 2022. This is not the best option for pine because beetles will infest the wood and emerge around June, 2021. Never stack green firewood next to live standing trees. This is inviting bark beetles to kill the standing trees when they emerge.

Decks of green logs stored through the winter are very likely to become infested in the spring if the inner bark is still moist. Snow cover and shade will increase the drying time.

Arborists Can Help Their Communities Prepare for Wildfires

By Michael S. Beaudoin

Community Forestry Program Manager

Before returning to Idaho to serve as the UCF program manager, I managed wildfire mitigation programs throughout California and Nevada. This background in wildland fire often informs how I provide technical assistance to our communities. The 2021 fire season in Idaho is shaping up to be a problematic one for our high-risk communities.

The relatively dry winter throughout the state resulted in record-low moisture levels in our forests and rangelands. Many of our communities are intermixed with this dry wildland and the urban canopy often abuts or is mixed with the wildland-urban interface (WUI).

The recent warmer weather is not helping matters either. The National Inter-Agency Fire Center (NIFC) in Boise predicts that our summer months will most likely be warmer and drier than typical for Idaho. More info on NIFC’s weather predictive services can be found here.

Although the 2021 fire season predictions look bleak, Arborists have many tools at their disposal to help their communities prepare for wildfires. Examining your city’s open space, golf courses, or multi-use trails for flammable untreated vegetation is a good place to start. 90% of fires start due to human-caused ignitions and municipal open space areas are often prime ignition sources. Inviting wildfire mitigation specialists to review your community forestry plan and identify priority treatment projects will help your community better prepare for potential ignitions.

Private arboriculture companies can also help prepare their communities for wildfire by assisting their clients with home-hardening services. Proper maintenance and irrigation of landscape trees are shrubs is crucial piece of wildfire mitigation. No tree or ornamental plant is completely fire-resistant especially when neglected by the home-owner. Some services our private contractors can provide include:

- Crown pruning tree branches at least 30 feet away from the home.

- Remove tree species that are highly flammable like Arborvitae.

- Remove leaf litter or debris from the roof and gutters of the client’s home.

- Install home hardening features such as ember-resistant vents

The University of Idaho and several other state extension services provide a lot of information on preparing your tree canopy for wildfires. Some helpful resources include:

- University of Idaho Cooperative Extension- Wildland Fire

- Idaho FireWise Program

- University of Nevada Cooperative Extension- Choosing the Right Plants for fire-prone areas.

Your home and the trees that surround it are most likely the biggest financial investment of your lifetime. Have you prepared to protect those investments? If you have questions regarding how Arborists can help their communities prepare better for wildfires assistance, please reach out to us at CommunityTrees@idl.idaho.gov

Consider Allergies Before You Plant

Approximately 50 million people suffer from seasonal allergies each year and approximately $18 billion is spent each year on addressing allergies (CDC 2018). All tree species produce pollen, but some produce much more than others. Trees that are wind-pollinated, like conifers, produce much more pollen than insect pollinated trees, like tulip trees (Liriodendron).

Much of our issues with allergies in our cities comes down to our tree selection and planting location. The recent trend of selecting male trees to avoid fruits falling on sidewalks has resulted in the planting of heavy pollen producing male trees.

Thomas Leo Ogren developed the Ogren Plant Allergy Scale (OPALS) in 2000 to classify trees by their pollen, contact, and odor allergy levels. When you plant, consider planting female trees or trees with a low pollen rating on the OPALS pollen rating scale.

Some tips on selecting allergy-friendly trees:

- Select Trees that with a OPALS rating of 5 or less (female red maples, female ash)

- Plant female-bearing plants to reduce the amount of pollen (Avoid female ginkgoes)

- Restrict outdoor activity during days that are windy with low humidity

- Shower after working outdoors to remove pollen from skin and hair.

For more resources on allergy sensitive trees please read this publication from the University of Florida here or the University of Nevada-Reno here.